The Auburn Cord Duesenberg Automobile Museum (ACD Museum) in Auburn, Indiana, focuses on preserving the history of the Auburn, Cord, and Duesenberg automobiles. They came to prominence during the Roaring Twenties as luxury automobiles. This is a terrific museum and is well worth the trip to Auburn, located in the northeast corner of Indiana. It has been listed as one of the top auto museums in the United States based upon Google reviews by transportmuseums.com.

The ACD Museum is in the former 1930 Auburn Automobile Company’s Administration building which included the showroom, company offices, and engineering and design studios. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. The showroom has been restored to its original grandeur with hand-painted ceiling friezes, three-tiered Italian chandeliers, a geometric terrazzo floor, a grand staircase and soaring showroom windows. The ACD Museum displays some of the most beautiful automobiles ever created—Auburns, Cords, and Duesenbergs—which in the 1920s were not only technological wonders but some also reflected the beautiful styling of Gordon Buehrig.

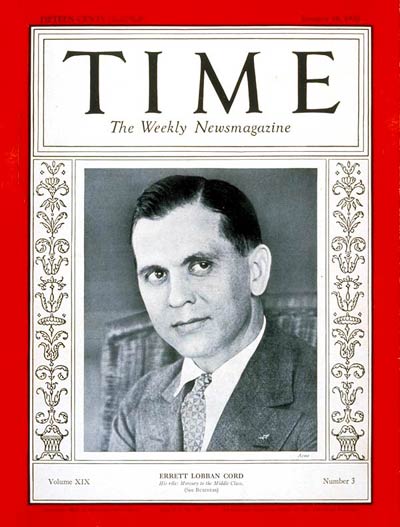

There would not be an ACD Museum without Errett Lobban (E. L.) Cord. Born in a small Missouri town, Cord’s family moved to Los Angeles when he was ten. As a teenager, he showed his interest in automobiles and entrepreneurial spirit buying Model T Fords, souping them up with more powerful engines, and racing them. He then sold the cars earning at least a $500 profit on each. He was a consummate marketer. It was his ability selling the Moon automobile for Chicago car distributor John Quinlan that led Quinlan to introduce Cord to the owners of the struggling Auburn Automobile Company.

Cord was on the cover of Time magazine on January 18, 1932

The Auburn Automobile Company traced its roots back to 1903 but had fallen on hard times. In the negotiations that followed, Cord convinced the company’s owners that he could turnaround the failing company. In return, the owners agreed that, if successful, he could buy a controlling interest. He was 31 years old when he became president of Auburn in 1925. For the next twelve years, he would become an icon of the American automobile industry.

He succeeded in his mission. In 1926, he established the Cord Corporation as a holding company for a variety of businesses. In 1927, he bought controlling interest in Duesenberg Motor Company which was in bankruptcy. Under his leadership, Duesenberg introduced the Model J in 1928. It was the most advanced car of that era with an engine that could produce 265 horsepower. That compares with the Cadillac whose engine produced 95 horsepower. The Model J was sold with only its chassis. The purchaser then contracted with a coachbuilder for the body. The cars were marketed to the uber-rich.

1929 Duesenberg Model J with body by the Walter J Murphy Company

In 1929, Cord introduced the Cord Automobile L-29, a subsidiary of the Auburn Automobile Company produced in Connersville, Indiana. Cord approached Harry Miller, who designed the 1925 Indianapolis 500 racer with front-wheel drive, to incorporate this technology into a passenger car. Cord was the first car manufacturer to offer front-wheel drive to the public. The Cord L-29 was designed by Alan Leamy with a profile eleven inches lower than other automobiles. A Cord L-29 was the pace car for the 1930 Indianapolis 500.

1930 Cord L-29

With the introduction of the Cord L-29, E. L. Cord had one fourth of the luxury brands (Cadillac, Marmon, Lincoln, Packard, Franklin, Stutz, and Duesenberg). With the Great Depression lingering on, and charges of stock manipulation of Cord Corporation’s subsidiary Checkered Cab Company by the Securities and Exchange Commission, the three automobile companies had failed by 1937.

In 1952, Herry Denhard, owner of an Auburn Speedster, put an ad in Motor Trend magazine seeking others wanting to preserve the history of Auburn, Cord and Duesenberg automobiles. This ad resulted in the formation of the Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Club. In 1955, a small band of Auburn, Cord and Duesenberg automobile owners gathered in Avon, Pennsylvania, for a “meet.” The next year, the club met in Auburn, Indiana, at the Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Company’s former headquarters. Amazingly, 600 people and their cars descended upon Auburn, Indiana, with a population of approximately 6,000. In 1969, the City of Auburn created the Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Festival which bills itself as the “World’s Greatest Classic Car Show and Festival.”

After production of the Auburn automobile ended, its showroom was taken over by Dallas Winslow who operated a parts and restoration company for Auburn, Cord, and Duesenberg automobiles until 1960. The building was then used for a variety of purposes including a machine shop, a garment manufacturer, and industrial warehousing. By 1970, the building was in disrepair.

In 1973, community leaders formed Auburn Automotive Heritage, Inc., a not-for-profit corporation to preserve the Auburn Automobile Company’s headquarters. They purchased the building in January 1974 for $105,000. The directors hoped to display up to 40 classic cars in the three-story, 80,000 square foot building. The remainder would be used for a variety of purposes including an auto restoration shop, a restaurant, and a place for the Tri-Kappa Collection of Auburn Automotive literature housed at the Eckert Public Library. Restoration commenced with a cost of $108,000 and the building opened to the public on Labor Day weekend, 1974 with a display of twenty-four borrowed automobiles in the 12,000 square-foot showroom. In August, the Museum received its first donated vehicle, a 1908 Zimmerman Runabout built in Auburn, Indiana. The second donated vehicle, a 1909 McIntyre Autobuggy which was also produced in Auburn, was donated in October 1974. Today, the museum has 140 automobiles on display.

The ACD Museum has nine galleries including one on other Indiana brands showcasing a variety of automobiles including an 1894 Black built by Charles H. Black in Indianapolis, an electric 1899 Waverley Stanhope Phaeton; a 1901 Haynes-Apperson; a non-production 1911 Izzer built in Peru, Indiana; a 1919 Cole Aero-Eight, a competitor to the Cadillac; a 1924 Marmon; a 1916 Premier: a 1923 Stutz Speedway Four and 1928 Stutz Blackhawk; and a 1932 Studebaker President.

It also has a gallery of cars produced in Auburn, Indiana, including a 1908 McIntyre, the successor to the W. H. Kiplinger Company. The ACD also has 1900 Eckert Spring Buggy (horse-driven), a predecessor to the Auburn Automobile Company.

Another gallery pays homage to Duesenberg’s racing history including a mock-up of the Hank Maley Gasoline Alley garage for the 1932 Indianapolis 500. Maley’s entry was the “Foreman Axle Shaft Special” Duesenberg driven by Freddie Winnai, who finished eighth in the race and one of the bricks from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

One of the surprises at the Museum is a 1931 Stinson Detroiter Junior 5 airplane originally owned by the Auburn Automobile Company. During the 1930s, it was displayed in the main gallery as it is today. This plane gives a nod to E. L. Cord’s involvement in the aviation business.

1931 Stinson aircraft

Cord Corporation was the majority owner (60%) of Stinson Aircraft between 1929 and 1934. Under E. L. Cord’s leadership, Stinson Aircraft became the largest producer of commercial market cabin planes. Another part of the Cord Corporation was Century Airlines which flew Stinson Model T trimotors on a commuter route serving Chicago, Springfield, and St. Louis, and Century Pacific which flew from Los Angeles to San Francisco, San Diego, and Phoenix. E. L. Cord had plans to expand the Century brand to other regional airlines. It also has the distinction of being behind the establishment of the ALPA, the world’s largest airline pilots’ union. Cord was in a wage dispute with the Century pilots and refused to negotiate. When the pilots went to work at Chicago’s Municipal Airport, they were greeted by armed guards who took them to a company official. The pilots were expected to sign a resignation letter and an application for reemployment at a lower wage. All the pilots refused to sign and were fired.